fast

fast

fashion

the fast fashion race to the bottom

by Cristina Gennari

21 settembre 2023

A solid-colored t-shirt for a casual outfit? On Shein, you can buy it for just 3 euros. And if the occasion is a smart dinner, you can simply connect to the new platform Temu to buy a long dress for less than 10 euros. The competition in the fast fashion industry is increasingly fierce, and the new Chinese giants, thanks to their offering of trendy clothing at extremely competitive prices, are revolutionizing the online shopping experience. It’s a cyclone that is testing well-established Western brands and redefining the global fast fashion market.

In this race to lower prices, the vast e-commerce platforms of Shein and Temu are contributing to consolidating China's leadership position, now the world's leading exporter of clothing. However, fast fashion is increasingly forced to grapple with new awareness related to environmental sustainability and social justice.

The Shein Model

The Chinese giant Shein, thanks to its ability to capture current trends and churn out new clothing at dizzying speeds, has established itself in the fast fashion industry over the past five years, becoming a global phenomenon capable of challenging industry-leading companies like Zara and H&M.

A climb that, according to the numbers, shows no signs of stopping, despite scandals and controversies. According to Bloomberg Second Measure's findings, Shein has increased its market share relative to fast fashion product sales in the United States from 12% in 2020 - the year the site began its ascent - to 50% in 2022.

Even in Europe, the ultra-fashion giant has achieved significant results, ranking first among the most downloaded fashion apps in the first six months of 2022. But that's not all. According to reports from The Wall Street Journal, a round of funding has brought the valuation of the Chinese e-commerce company to 100 billion dollars, which is higher than its main competitors (the Swedish H&M and the Spanish Inditex) combined.

The Most Downloaded Fashion Apps in Europe

Shein stems from Nanjing Dianwei Information Technology Co. Ltd, founded in 2008 in Nanjing, eastern China, by three individuals, including Xu Yangtian, also known as Chris Xu. At that time, the company primarily dealt with wedding dresses, but in 2012, Chris Xu decided to focus entirely on a new women's clothing brand by acquiring the domain Sheinside.com, renamed Shein in 2015.

The headquarters, Guangzhou Xiyin International Import & Export, has been in southern China since 2017, specifically in the metropolis of Guangzhou, where most of the supplier factories are concentrated. The headquarters belongs to the Hong Kong-based company Zoetop Business, which also manages the international rights of the Shein Group brands and e-commerce activities.

No stores, except for temporary stores. The brand relies entirely on digital, selling affordable clothing on its e-commerce platform with the (stated) mission of making fashion accessible to everyone, not just a few privileged individuals. Its secret is constantly introducing new collections into the market, leveraging the algorithms' ability to identify the latest trends before competitors.

By acquiring information about its users and current trends, Shein is even capable of discovering what we might want to wear, perhaps even before we do. Production, as explained to Il Sole 24 Ore by Peter Pernot-Day, global head of strategy and corporate affairs at Shein, is based on an 'on-demand manufacturing' model. Practically, the company produces up to 200 units of new products, which it introduces into its virtual market, and then adjusts production based on demand. A strategy that, at least for now, seems to have rewarded the Chinese brand, which exploded during the pandemic and remains an absolute protagonist in the fast fashion market, despite its growth slowing due to various scandals.

Shein has indeed been at the center of a series of controversies that have highlighted its unsustainable environmental impact and some worker exploitation practices. The self-promotion campaign organized by the Chinese giant, which invited a group of influencers and creators to its factory in Guangzhou, did little to improve its image: many thought it was a clumsy attempt at greenwashing. Although investigative journalism is on the rise and the brand's reputation is declining, thousands of users continue to shop on the Chinese e-commerce platform every day and unbox their purchases in videos posted on TikTok.

Global Downloads of the Shein App

Financial health of the fast fashion industry

Today, the fast fashion market, according to estimates from the research and analysis company Statista, is worth over 120 billion dollars globally. Despite the alarm raised by activists and environmentalists, the doors of our closets and store shelves continue to fill with trendy clothing, and the fast fashion industry continues to thrive – by 2027, it is expected to surpass 184 billion dollars.

But let's take a step back. It was December 31, 1989, when an article titled 'Two New Stores That Cruise Fashion's Fast Lane,' by journalist Anne-Marie Schiro, was published in The New York Times. The occasion was the opening of two new boutiques on Lexington Avenue that catered to 'fashion-conscious young people on a limited budget who change their clothes as often as the color of their lipstick.'

Among the openings, the standout was the first Zara international store in the city, located at the corner of 59th and Lexington, selling items ranging from $5 for knit gloves to $145 for a coat with faux fur collar and cuffs, as well as metallic knit skirts and dresses for $27 and $43, and Shetland wool sweaters for $53.

The concept of the new business was clear: change the inventory in the store every three weeks and chase the latest trends. After all, it only takes 15 days for a garment to go from the design phase to store shelves. This was the first time the term 'fast fashion' appeared. Yet, the conquest of fast fashion had already begun. In 1947, the H&M chain was born, followed by the Irish brand Primark in the 1960s, and just a few years later, in 1975, Zara opened in La Coruña. Later, the Inditex holding company was created, which now owns Zara as well as Pull&Bear, Massimo Dutti, Bershka, Stradivarius, and Oysho.

However, it was between the late 1990s and the 2000s that low-cost fashion reached its peak, thanks to its ability to produce dozens of new collections each year, often replicas, at more affordable prices than models from famous fashion houses. It was a way of democratizing fashion, making products and trends previously reserved for the privileged few accessible to everyone.

Forever 21, Uniqlo, Gap, Boohoo, Fashion Nova, and many others. The fast fashion market, which soon evolved in ultra-fashion, is a rapidly-changing industry characterized by the proliferation of new players. In recent years, especially Chinese players like Shein and, to some extent, Temu, have been trying to capture a significant share of the sector, challenging some established Western companies like Inditex, H&M, and Mango. Thanks to their ability to combine the latest trends with affordable prices, the recent Chinese cyclone is making the competition increasingly intense and posing new challenges to the fashion industry.

Revenues and profits of the main fast fashion companies in 2022

Although the current industry must grapple with increasing awareness of sustainability and a fierce price war, the state of fast fashion is still robust. Confirmation of the market's strength also comes from the financial statements of industry giants.

The leading group, Inditex, closed the 2022 fiscal year with revenues of 32.6 billion euros, a growth of 17.5% compared with the previous year. Positive results were also reported by the Swedish competitor H&M, with sales amounting to 223.5 billion Swedish crowns, approximately 20 billion euros, and a net profit of 320 million euros. Unofficial figures reported by The Wall Street Journal regarding Shein are significant: in 2022 the Chinese giant reportedly generated 23 billion dollars in revenue.

Even in the first half of 2023, Inditex confirmed its solid operational performance. Revenue reached 16.9 billion euros, with a significant 40.1% increase in net profit. Sales grew by 13.5% compared to the same period of the previous year, while Ebitda increased by 15.7%, reaching 4.7 billion euros. Net profit also increased by 40.1%, reaching 2.5 billion euros.

The Irish chain Primark also has positive results, and it expects a 15% improvement in sales for fiscal year 2022-2023 compared with 2021-2022, as disclosed in a statement by the parent company Associated British Foods. In absolute terms, this translates into annual sales of approximately 9 billion pounds. A healthier-than-ever business, as confirmed by an ambitious international expansion plan: by the end of the fiscal year, Primark plans to operate in 432 stores, with a total selling area of 1.69 million square meters.

However, the entry of new players and the ruthless competition from fast fashion rivals, from Inditex to Shein, is starting to put pressure on the stability of some old fast fashion giants. Reuters predicted that in the third quarter of 2023, H&M's net sales have increased by 6% to SEK 60.9 billion (approximately 5.1 billion euros), but this is a 'flat' growth, lower than the 63.5 billion expected by analysts.

The value of the fast fashion market

Value of the second-hand clothing market

The fast fashion business keeps growing. According to forecasts, the value of the segment could even increase by 50% in the next four years. However, in recent times, the industry has had to grapple with growing environmental awareness and more sustainable shopping habits. Consumers are becoming more critical in their purchasing choices and more interested in eco-friendly and ethically-made products.

The fast fashion format, which floods the market with huge volumes of products - in 2022 alone, the Inditex group placed 621,000 tons of items - to encourage continuous shopping seems to be no longer convincing. More eco-friendly practices are in fact becoming more popular: the global value of the second-hand clothing market could surpass 350 billion dollars by 2027.

But that's not all. In the ranking of the most downloaded fashion apps in Europe during the past year, behind the unbeatable Shein, the popular second-hand clothing e-commerce platform Vinted stands out.

Temu, the rise of the new Chinese e-commerce

On February 12, the world was watching the most emblematic sports event of American culture, at the State Farm Stadium in Glendale, Arizona. But while the Philadelphia Eagles and Kansas City Chiefs battled for the NFL title, the professional American football league, a new (and unexpected) protagonist drew attention at the Super Bowl.

No, we are not talking about Rihanna, although the pop star performed her famous hits like "Bitch Better Have My Money" and "Rude Boy" on futuristic suspended platforms during the highly anticipated halftime show. With a 30-second commercial that aired during the first and third quarters of the final, created by the agency Saatchi & Saatchi and directed by Robert Jitzmark, the latest "Made in China" shopping app, Temu, made its debut in the Western market.

Its calling card? A curly-haired woman, engrossed in endless scrolling on her smartphone, adding to her cart and wearing a long series of extremely inexpensive clothes and accessories with the paradigmatic slogan 'Shop like a Billionaire'.

However, Temu is far from being a platform for billionaires. From electronics to home accessories, from makeup products to clothing to a variety of miscellaneous items, it features a wide range of products with one common denominator: bargain prices. In other words, an expansive virtual marketplace with the ambition of establishing itself in the fast fashion ecosystem and the broader online commerce, following in the footsteps and challenging giants like Shein and Amazon.

The new platform, launched in the United States in September 2022, is Pdd Holdings’, the Chinese digital economy giant that owns the well-established e-commerce Pinduoduo, a significant player in the domestic market in direct competition with Alibaba and JD.com.

In May, the group made a significant strategic move by relocating its executive headquarters from Shanghai to Dublin, Ireland, to take advantage of more favorable tax policies. After its American debut, the Pinduoduo spin-off has launched its foreign offensive, primarily targeting the Western market, rapidly spreading and becoming one of the most downloaded apps in the world. In April, Temu arrived in Belgium, France, Germany, Poland, and the United Kingdom before becoming available in other countries like Italy, Austria, Finland, Greece, Ireland, Luxembourg, and Slovakia.

The success of Temu can be attributed to its business model, which leverages supply chain shortening and an especially invasive advertising strategy. But let's take a step back. The name Temu reflects the company's concept: Team Up, Price Down. The goal is to incentivize extreme shopping with a simple and automatic mechanism: the more users buy the same product, the lower its price becomes.

Global downloads of the Temu App

The result is an innovative shopping experience that is based more on discovery than on search: potential customers are recommended products that should match their interests and preferences, meticulously curated by an algorithm. All this is seasoned with a dose of gaming and entertainment, following the so-called shoptainment model. Coupons, discount codes, time-limited offers, and mini-games to earn virtual credits make up a long list of benefits that trigger a virtuous cycle but, of course, have the sole objective of making us buy more and at increasingly advantageous prices.

On the other hand, the competitive advantage of the new e-commerce giant lies in its ability to cut costs by directly connecting producers with customers in Western countries. Physical or virtual stores, as well as distribution warehouses, have been abolished, resulting in products being offered at factory prices. A women's dress? In the cart for just 3 euros. And for a modern smartwatch, only a 10-euro bill is needed.

The gross merchandise value (GMV) of Temu

While the newcomer marketplace with its diverse range of items is climbing the charts and markets worldwide, challenging established giants, the most challenging battle is being fought in the fast fashion arena. Temu has taken the titanic competitor Shein to court, accusing them of violating antitrust laws by prohibiting suppliers from working with the new platform.

On the other hand, the ultra-fast fashion giant has sued Temu, alleging trademark and copyright infringement and false and deceptive business practices. While awaiting the judges' decisions, competition in the fast fashion market appears fiercer than ever, with the Chinese whirlwind reshuffling the deck with unbeatable prices.

The race to the bottom in fast fashion

The fast fashion industry has revolutionized the way we buy clothes. The ability to offer a wide selection of products at low costs has made fashion more accessible to a broad audience of buyers, allowing people to follow the latest trends without spending much.

The increasingly fierce and globalized competition among brands and companies, the economic crisis, and the wide range of clothing and accessories, often interchangeable among them, in recent years have intensified the competition in the fast fashion market, effectively fueling a 'price war'.

Making this challenge even more intense, modern players like giant Shein and the newcomer Temu are dominating the ultra-fast fashion ecosystem with their ability to maintain competitive prices, forcing competing brands to navigate the race to the bottom.

But let's look at the numbers. A deeper comparison of prices on the e-commerce platforms of the leading brands in the sector paints a picture of extreme competition played out with incredibly reduced figures.

Consider, for example, that to get a complete casual outfit, including a T-shirt and blazer, jeans with a belt, and sneakers (comparing similar products and taking into account the most advantageous price available on each site), it costs less than 60 euros on half of the considered marketplaces. This amount drops significantly when observing the large Chinese retailers: to purchase items from Temu, only 28.62 euros are needed, and with just 24.75 euros, you can fill your cart with Shein products.

The race to the bottom becomes even more clear when analyzing a basic solid-color T-shirt. Among the observed companies, the highest expense is incurred when buying from the Spanish brand Mango, although in practice, just 8.99 euros are enough. However, on the Shein and Temu platforms, with their wide-ranging offerings that encompass fashion and more, a mere 3.40 and 2.77 euros respectively can get you an equivalent product, beating even a low-cost clothing leader like Primark (3.50 euros).

Comparison of prices for a complete outfit among the main fast fashion e-commerce platforms

The fight to offer lower prices is obvious and is pushing brands and retailers to constantly find new ways to reduce their costs and remain competitive in a market that often rewards those who offer the most attractive deals.

And if dealing with the ruthless competition of ultra-fast fashion seems unthinkable, some 'old' fast fashion brands are rather aiming to reevaluate their positions and partially reverse their strategies. In an effort to raise their target and prices, various brands have initiated and are initiating quality projects, as proven by the partnership between H&M and designer Heron Preston and the exclusive collection created by Zara with photographer Steven Meisel.

But that's not all. The business dynamics and consumer expectations in the era of online shopping, especially among younger generations who seem more inclined to replace their clothes with new ones, embracing the latest trends and fostering a 'use and throw away' culture, are also influencing pricing strategies. Traditional brands tend to offer discounted products only through seasonal promotions, meaning that consumers have to wait for specific periods to take advantage of sales. On the other hand, the strategy of maintaining constantly discounted prices, adopted by Shein and Temu and an increasing number of retailers in the retail industry, is a systematic tactic aimed at creating a continuous sense of value for consumers and stimulating compulsive buying.

Furthermore, while several companies like Zara, OVS, and Alcott keep clothing items constantly available on their virtual shops, ensuring a steady supply and minimizing depletion, the inventories of products in Chinese marketplaces are limited and destined to run out.

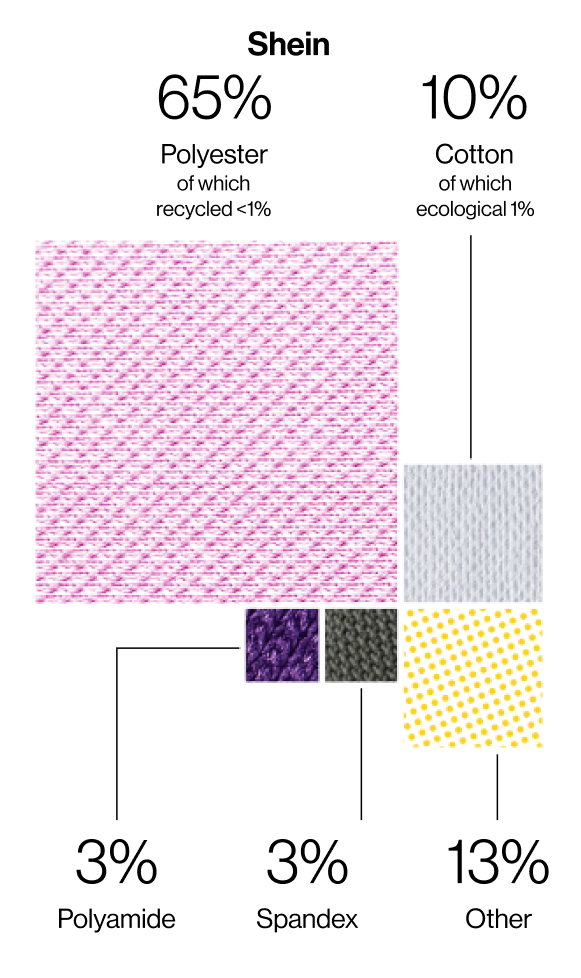

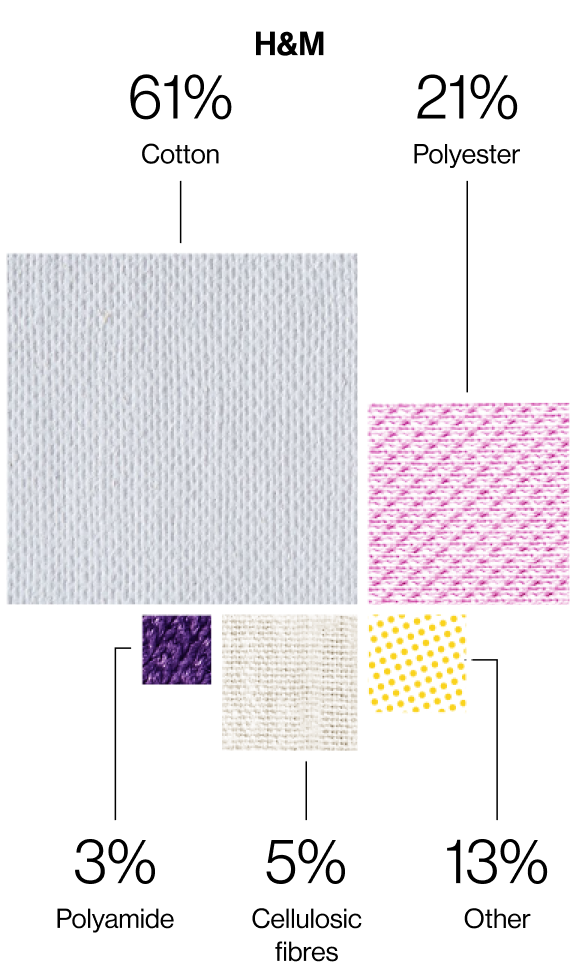

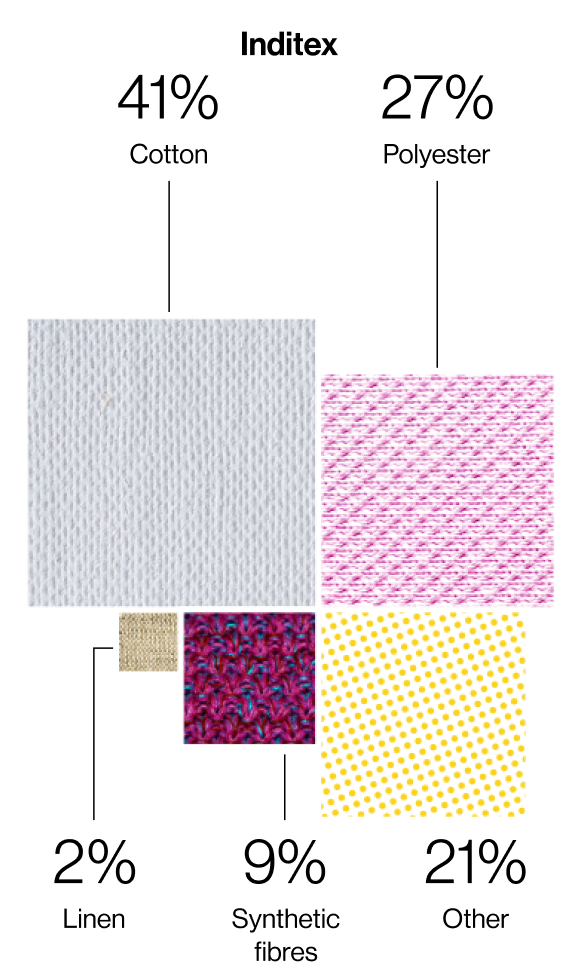

Similar yet different items. The investigation conducted on different e-commerce platforms highlights another difference: the composition of similar products varies significantly among brands. Take a T-shirt, for example. While on Shein and Temu the T-shirts for sale are mainly made of polyester, those available on the stores of brands like Mango, Zara, and OVS are mostly composed of cotton. This key evaluation element, in the frenetic race to lower prices, could guide quality and sustainability-conscious consumers' purchasing decisions.

The social success of apps that appeal to Gen Z and Millennials

On TikTok, the hashtag #Shein has garnered over 73 billion views. Just a year after its launch, #Temu has reached 4.8 billion. The success of these Chinese giants, and the entire fast fashion industry, is driven (and primarily so) by social media. These multinational companies are forcefully establishing themselves in the fast fashion and online shopping segment, thanks to their appeal to younger customers. The ability to keep up with trends and offer competitive prices, combined with a strong online presence capable of integrating e-commerce and social media, is their formula for success.

Their marketing strategy is primarily based on advertising campaigns on platforms like Instagram and TikTok and collaborations with thousands of micro-influencers to whom free clothes and discount codes are sent for their followers. But it also relies on a popular practice on social media, known in modern slang as a 'haul.' Literally, it means 'booty,' and it refers to videos or posts in which more or less known influencers and shopping enthusiasts unpack their recent purchases, often replicas of trendy items of the moment, showing them off and wearing them to allow viewers to see how they look and fit in real-life contexts.

It's a simple trend, but it creates an emotional bond between the brand and its audience, who appreciate the sharing of authentic content and the ability to identify with similar lifestyles. Not surprisingly, on the pages of Shein and Temu - which have 30 million and one million followers on Instagram, respectively - user-generated content abounds, making the brand narrative more natural and, above all, the products more desirable.

But while videos of so-called 'dupes' - a term that refers to products or clothing items that mimic luxury or expensive brands in a more affordable way - and comparisons between Shein, Temu, and other brands are spreading, especially on TikTok, there are also more critical voices that are trying to draw attention to the darker sides of Chinese giants and ultra-fast fashion.

The fenomeno ‘haul’ phenomenon takes over TikTok

The likes and interactions that Shein and Temu are getting on social media are clear evidence of the growing popularity that these brands, as well as the entire fast fashion industry, enjoy among Generation Z and Millennials.

These retailers are intercepting the tastes and needs of young consumers, who are looking for trendy items at affordable prices. According to the numbers, over 56% of visitors to Shein's website are under 34 years old, while the demographic group that connects most with Temu's e-commerce are individuals between 25 and 34 years old (22.07%).

This success is far from random. Through advanced algorithms, these brands collect data from their website and app users, allowing them to anticipate and immediately understand the preferences of their target audience. All of this is done to give young users what they desire and offer highly personalized experiences, key elements of their success.

The target audience of Shein and Temu

The legal battle

Despite their success and rapid ascent, the fast fashion industry is not exempt from legal controversies, especially regarding copyright violations. Over the years, many prominent brands in the sector have faced accusations of plagiarism and misappropriation, particularly from designers and creatives.

The unauthorized reproduction of patterns and graphics, which undermines the creativity and work of artists and companies, raises significant questions about intellectual property rights in the fashion industry and prompts critical reflection on ethics and legality in the fast fashion segment.

Among all, Chinese e-commerce platforms and their suppliers, with Shein at the forefront, have faced numerous criticisms for intellectual property infringement in the United States, becoming the subject of a series of legal cases, many of which are still pending. According to the Wall Street Journal, in 2022 there were over 50 pending federal proceedings against Shein.

The Trend Pollution

The fashion industry is among the most polluting in the world. Each year, it uses 93 billion cubic meters of water and is responsible for a significant share of greenhouse gas emissions, estimated at 8 to 10% of the global total.

This unsustainable impact has intensified in recent years with the rise of fast fashion. Its business model has amplified resource consumption and waste production. It is estimated that between 80 and 100 billion new garments are produced each year, about 14 per person on Earth, most of which are destined for increasingly shorter life cycles. In the European Union alone, according to Commission data, 5.2 million tonnes of clothing and footwear waste are generated each year, equivalent to 12 kg per citizen.

The result is that every second, a truckload of clothing is dumped in a landfill, often on the other side of the world. Places like the Atacama Desert in northern Chile or African nations like Ghana and Kenya bear the brunt of textile waste, including used and often unsold new items, spanning approximately 741 acres of T-shirts, shirts, jeans, and garments.

Yet, the production of clothing, especially in the fast and ultra-fast segments, requires considerable resources. The production of a pair of jeans, for example, requires 3,781 liters of water when considering the entire supply chain, from cotton cultivation to the delivery of the final product to the store. In 2022 alone, a fast fashion giant like Inditex consumed 1,780,190 cubic meters of water.

How Much Water is Needed

The fibers used in the production of garments are another important indicator in terms of sustainability. Polyester, which has become the most widely used material in the world due to its cost-effectiveness and versatility, requires substantial resources - it is produced from fossil fuels and often mixed with other fibers - and is difficult to recycle.

The environmental impact of cotton, the second most used fiber in fashion, is also significant. It is, in fact, the crop with the highest water footprint.

Fibers used by major fast fashion companies

However, synthetic fibers like polyester, nylon, and acrylic, which are used by many low-cost brands - now accounting for about 60% of the material that makes up our clothing - raise another issue: the unintentional release of microplastics into the environment.

During the washing of synthetic fabrics, small plastic particles - less than 5 millimeters long, with diameters measured in micrometers - can detach from the garments and end up in water networks, before settling at the bottom of seas and oceans. According to estimates, the washing of synthetic clothing accounts for 35% of primary microplastics released into the environment, and a single load of polyester laundry can release up to 700,000 microplastic fibers.

From the extraction of textile fibers to the shipping of garments and their washing by consumers, the ecological footprint of the industry also depends on greenhouse gas emissions. In 2020 alone, textile product purchases in the European Union generated approximately 270 kg of CO2 emissions per person.

These substantial figures are confirmed by data related to Scope 1, 2, and 3 emissions from major fast fashion retailers. As reported in sustainability reports published by these companies, in 2022, the Inditex group generated over 17 million metric tons of CO2 emissions, while the Chinese competitor Shein declared more than 9 million metric tons, including both direct and indirect emissions.

CO2 emissions of major fast fashion companies in 2022

Towards a more sustainable industry?

More durable clothes that are also easier to reuse, repair, recycle, and ultimately dispose of. And a production process that respects human, social, and labor rights, as well as the environment and animal welfare. All by 2030. The European Union's strategy for textiles, presented in 2022, embraces the need for a more sustainable industry and sets a series of goals to be achieved by the end of the decade.

From ecodesign to the issue of microplastics, including the fight against counterfeiting and the fast fashion industry. The key themes at the heart of the European action plan for the textile sector are numerous, although the actual impact of directives on fast fashion remains uncertain.

Many fast fashion brands are trying to adapt to the growing demands of sustainability. Recycling programs, environmentally conscious production processes, and greater social responsibility are becoming integral parts of the strategies of the sector's major players, albeit at different paces. For a more in-depth analysis of progress and efforts in reducing environmental and social impact, we have examined sustainability reports published by major fast fashion retailers. Although the documents differ significantly in content and transparency, what emerges is a growing green approach.

The race for renewables

According to what has been declared, the giant Inditex has indeed achieved significant results in 2022, including 100% of electricity used coming from renewable sources and total waste reduction at its facilities. In the medium and long term, ambitious goals have been announced: a 25% reduction in water consumption in the supply chain by 2025 and net-zero emissions by 2040.

Swedish company H&M is also making significant strides in terms of sustainability: in 2022, 23% of the materials used were recycled, and the stated goal is to reach 30% by the end of 2023. But that's not all. The brand aims to reduce CO2 emissions by 56% by 2030.

Even Shein, often associated with polluting and non-transparent practices, outlines clear goals in terms of environmental responsibility in its Sustainability Report. The company plans to convert at least 31% of its polyester-based products into recycled polyester by 2030 and aims to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 25% by the same year.

As for its rival Mango, in 2022, 46% of its fibers came from natural sources, and 11% from recycled fibers. By 2030, the company aims to reduce 80% of scope 1 and 2 emissions and 35% of scope 3 emissions, as well as a 25% reduction in water impact.

Irish fast fashion leader Primark aims to reduce carbon emissions throughout the supply chain by 50% by 2030 and eliminate single-use plastics by 2027.

In addition to actions to limit the environmental footprint, an important game is being played on the circular economy front. Many fast fashion industry leaders are launching programs to extend the lifespan of their products. For example, H&M has implemented the Garment Collecting initiative, which in just one year in 2022 collected 14,768 tonnes of used products, of which 55% were reused as products, 15% as materials, and 22% recycled into products for other industries or new fibers.

The Most Transparent Fast Fashion Brands

One of the key words in the challenge to make the fashion industry more sustainable is 'transparency.' Many companies are adopting a series of measures to clarify their production processes, from the sources of materials to the conditions of workers.

This trend aligns with the approach of the European Commission, which intends to introduce a 'digital product passport' to allow consumers to access information about the origin and sustainability of the clothing they purchase.

However, there are already key tools that provide analysis of the transparency practices adopted by fashion brands. Among these is the 'Fashion Transparency Index,' which ranks 250 of the world's largest fashion brands and retailers based on their public disclosure of policies, practices, and impacts on human rights and the environment. And, as the assessments for 2023 show, while some companies in the fast fashion market, including OVS, are responding promptly to the call for greater transparency, other industry leaders still have some shortcomings.